Book Review Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World by Alexandra Libby, Brooks Rich, and Stacey Sell (editors) with essay by Brian W. Ogilvie - Review by Julianne Snider

More than two thirds of this lovely publication is filled with full pages of images and details of the watercolors, oil paintings, etchings, engravings, and woodcuts selected to illustrate Little Beasts’ central themes: the evolution of natural history in Europe beginning in the 15th century, and the work of Joris

Hoefnagel and Jan van Kessel the Elder, two Flemish artists and contributors to the discipline of descriptive natural history during the 16th and 17th centuries.

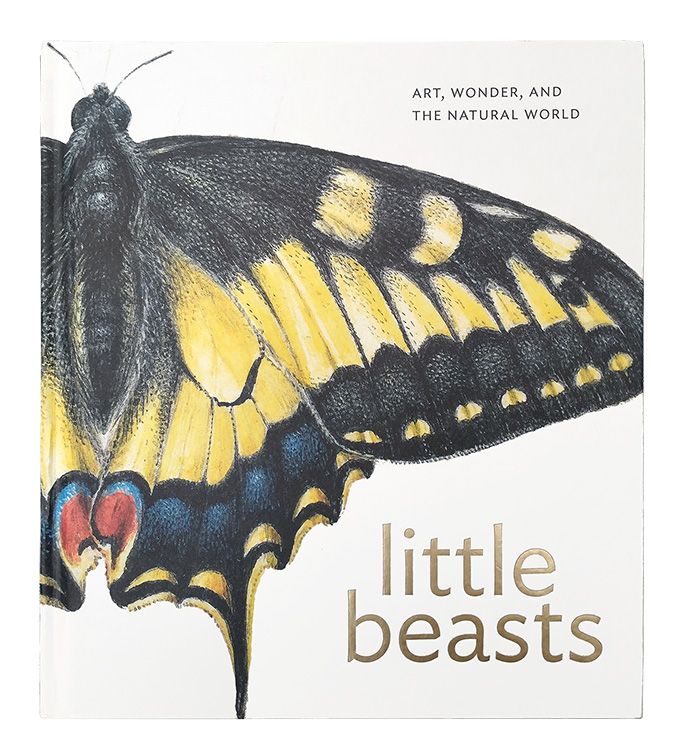

Cover of Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World

By Alexandra Libby, Brooks Rich, and Stacey Sell (editors) with essay by Brian W. Ogilvie. Published: May 20, 2025 by The National Gallery of Art in association with Princeton University Press

Several illustrations of work by Dürer, Hooke, Aldrovandi, Gessner, Bol, di Liagno, and others are included in the publication to highlight the types of images that were being produced and incorporated into the growing number of books being acquired by universities, naturalists, collectors, catalogers, and classifiers of animals, plants, and minerals as interest in natural history grew during the Renaissance period of Western Europe. These illustrations and books played a significant role in disseminating information about exotic, non-European flora and fauna that were being brought into Europe from all over the world. Illustrations, reprinted in multiple publications and copied multiple times by multiple artists, were sought after by collectors and creators of cabinets of curiosity.

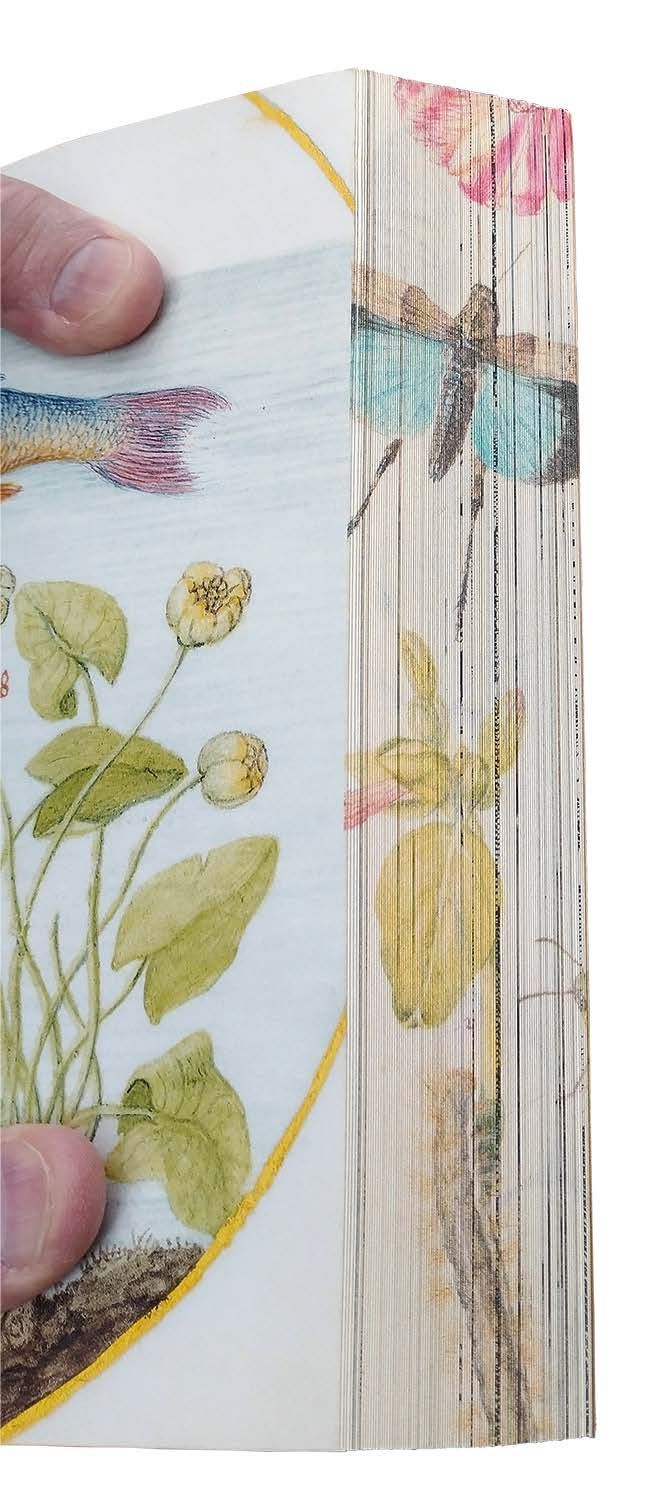

Hoefnagel (1542–1601) and van Kessel (1626–1679) accessed these prints and publications as they explored the intersection of art and science through their interests in depicting denizens of the natural world—insects, reptiles, mammals, fish, birds—as realistically as possible. Images from these artists’ brushes are included as endpapers, as hidden double fore-edge paintings under the gilt edges of the book block, as delightful little beasts crawling across pages of text, and as full-page cited illustrations plus details from their works of art.

Jan van Kessel the Elder, Insects and a Sprig of Rosemary, 1653, oil on copper. 4.5" x 5.5"(11.5 x 14 cm) National Gallery of Art, The Richard C. Von Hess Foundation, Nell and Robert Weidenhammer Fund, Barry D. Friedman, and Friends of Dutch Art. 2018.41.1

Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World was published as the companion to the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., exhibit of the same name. The exhibit, curated by Alexander Libby, Brooks Rich, and Stacy Sell, was comprised of specimens from the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, 80 works of art, and The Four Elements—four volumes containing hundreds of Joris Hoefnagel’s original watercolors on parchment from the drawing collection of the National Gallery. Several images and details of Hoefnagel’s original watercolor paintings from the volumes are included in Little Beasts the book. The original paintings in the volume Ignis (fire) are life-size depictions of insects, sometimes incorporating complete dragonfly wings or transfer prints of butterfly wings—a technique known as lepidochromy. Images in the other three volumes, Terra (earth), Aqua (water), and Aier (air), are miniatures of multiple animals depicted in somewhat naturalistic settings and classified by the element in which they were found. Terra covers “elephants to insects”, Aqua has “water animals”, and Aier includes birds and bats. Ignis, inexplicably, is the element containing primarily insects. The illustrations in Ignis were painted directly from live or preserved insects. Animals depicted in the other volumes were copied mostly from other sources and arranged to create vignettes enclosed in ovals drawn with gold paint. The insects are also arranged aesthetiacally and framed in gold ovals. The Four Elements was created as a personal project by Hoefnagel that he shared with friends and colleagues.

Joris Hoefnagel, Hairy Dragonfly and Two Darters (Ignis, Plate 54), c.1575/1590s. Transparent and opaque watercolor, dragonfly wings, oval border in gold on parchment. 5.625”x 7.25” (14.3 x 18.4 cm). National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mrs. Lessing J. Rosenwald 1987.20.5.55

Detail of Ignis, Plate 54, (lower right Darter) showing dragonfly wings (degrading) adhered on top of watercolor painting of body and shadow.

In his opening essay “Natural History in the European Renaissance” Brian W. Ogilvie, professor and chair of the Department of History at University of Massachusetts Amherst, takes the reader through the origins and early advancements of natural history. Ogilvie reminds us of the fundamental role art played in the development of the new science of studying the natural world while pointing out that the curiosity and wonder driving the growth of science and art during Europe’s Renaissance period were fueled by the flood of unfamiliar plants, animals, pigments, and other goods coming into Europe from colonial and commercial expansion and exploitation—there is a moral cost of curiosity that deserves awareness and recognition.

Stacey Sell, associate curator of old-master drawings at the National Gallery, provides an overview of the artists and scientists who influenced the life and work of Joris Hoefnagel in her chapter “‘Through Such Variety, Nature is Beautiful’: Joris Hoefnagel,

The Four Elements, and Natural History”. Sell covers details about the references, techniques, and materials Hoefnagel used to create his paintings in

The Four Elements. For

Ignis, Hoefnagel departed from the then-customary themes of natural history to concentrate on the uncharted topic of little beasts, i.e., insects. Along with his use of watercolors to illustrate these little beasts, Hoefnagel experimented with the use of metallic paints to create the look of iridescence, the use of tinted resins and gums to impart shine to insect eyes and wings, the incorporation of wings and scales in depictions of Odonata and Lepidoptera, and painting insects on blank backgrounds where the shadows they cast were painted in to create a life-like quality to the illustrations.

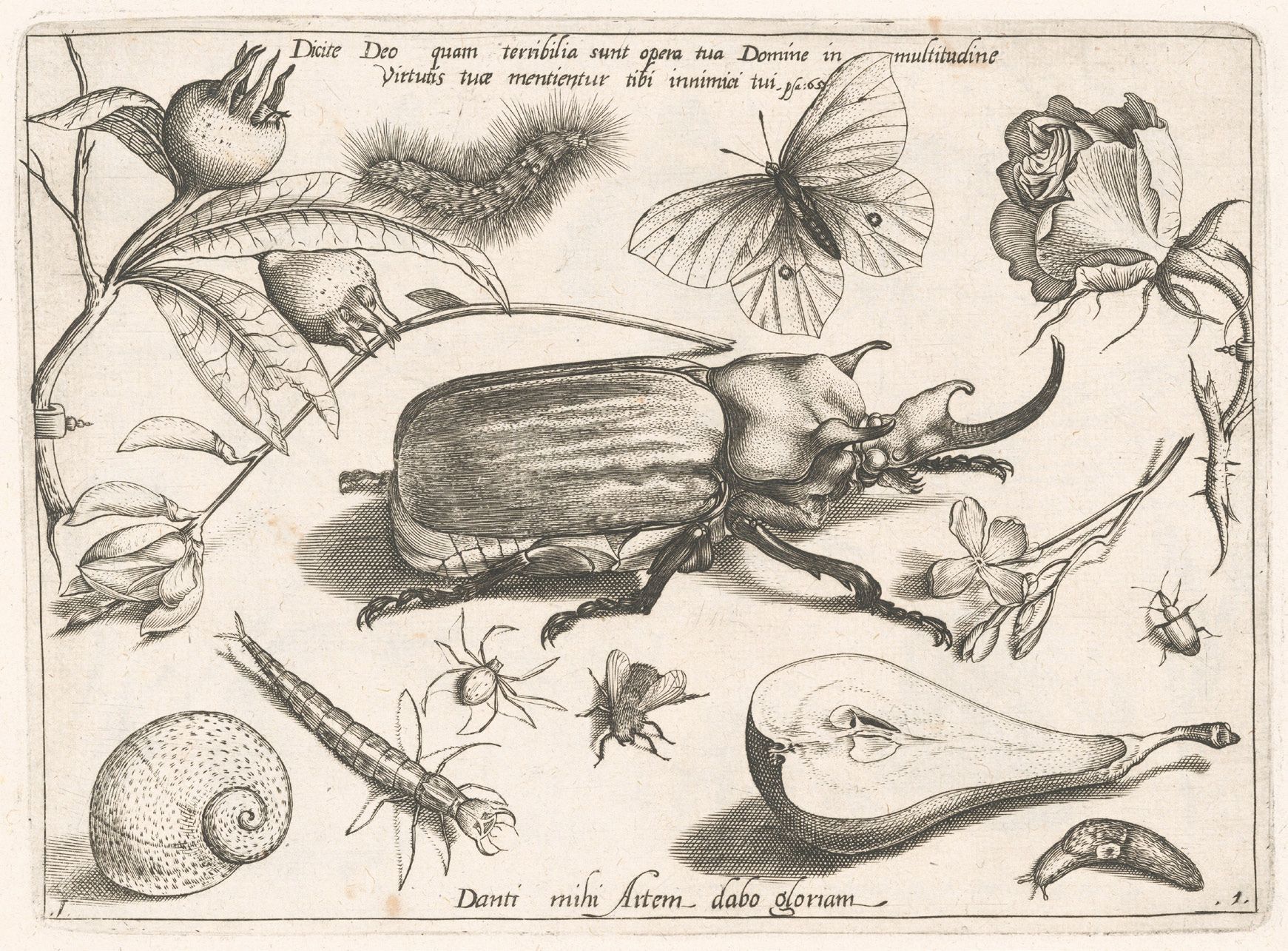

Jacob Hoefnagel, after Joris Hoefnagel, part 1, plate 1 from Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii, 1592, engraving 6.125” x 8.1875” (15.5 x 20.8 cm). National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mrs. Lessing J. Rosenwald. 1987.20.9.2

In the chapter “Survival of the Finest: Animals in Early Modern Intaglio Print Series”, Brooks Rich, associate curator of Old Master and 19th century prints at the National Gallery, looks at Hoefnagel’s move toward monetizing his original work through use of the intaglio printmaking techniques of etching and engraving. Working with his printmaker son, Jacob Hoefnagel, the images printed were not direct copies from images in The Four Elements but compositions depicting animals and little beasts with plants and other creatures. The Hoefnagels’ approach diverged from the style of animal prints of the time with the inclusion of “flower, fruits, and nuts” and a selection of other organisms. Beginning in 1592, a series of these compositions were reproduced and made accessible and affordable to a wide audience including print collectors. Hoefnagel was just one of several artists of his time to embrace working with printmakers. Rich provides a history of the growth of printmaking and use by artists through the 17th century and points out how creating and distributing prints of original work provided many artists with a source of income, increased fame, and contributed to their legacy. The distribution of printed images also contributed to growth and transfer of knowledge and natural history as a discipline.

Circle of Jan van Kessel the Elder, Study of Birds and Monkey, 1660/1670, oil on copper, 4.25” x 6.75” (10.5 x 17.2 cm). National Gallery of Art, Gift of John Dimick. 1983.19.1

Alexandra Libby, senior administrator of collections and initiative for the National Gallery of Art, provides the closing chapter “‘Monstrous Creatures and Diverse Strange Things": The Art of Jan van Kessel”. Van Kessel was a talented painter, a member of the renowned Brueghel family of artists, and was registered as an apprentice in the Antwerp Painters Guild when he was eight years old. Born well after Joris Hoefnagel’s death, van Kessel was nonetheless influenced by Hoefnagel’s work and became a celebrated painter of insects and little beasts in his own right. Van Kessel painted his insects life size on postcard-size copper plates using oils and metallic pigments. Painting from real, possibly some live, specimens van Kessel depicted insect behaviors, sexual differences, life stages, non-European insects, and groups of different species together along with plants, shells, and other creatures. Although it is not known what magnification tools van Kessel may have used, it is likely that he had access to advanced optical technologies that were not available during Hoefnagel’s life. Van Kessel worked during a time of “early modern luxury culture” when premiums were paid for rare, foreign, and finely crafted items that collectors wanted to include in their rooms and cabinets of curiosities. About 120 van Kessel small paintings on copper are known to still exist out of the more than 700 he created. Libby points out that van Kessel’s work in natural history was an extension of the tradition of exchanging of ideas, observations, and knowledge between artists and natural scientists.

This book, Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World, is a pleasure to hold, flip through, closely look at the multitude of illustrations, as well as read. The list of illustrations provides useful information on materials used by the various artists represented. Little Beasts should be of interest to artists, illustrators, art historians, historians of science and natural history, and book arts enthusiasts. Available as a hardback and in electronic formats, Little Beasts the book will remain relevant and memorable long after Little Beasts the exhibit has been taken down and packed away.

Edge painting on the pages of the book.

Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World

By Alexandra Libby, Brooks Rich, and Stacey Sell (editors) with essay by Brian W. Ogilvie

Published: May 20, 2025 by The National Gallery of Art in association with Princeton University Press

224 pages, 150 illustrations, Size: 8 x 9 inches Hardcover: ISBN 978-0-691-27130-9 Ebook: ISBN 978-0-691-27131-6

Available in hard copy or electronic form from: The Gallery Shop, National Gallery of Art. https://shop.nga.gov/little-beasts-art-wonder-and-thenatural-world and from

Princeton University Press: https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691271309/little-beasts?srsltid=AfmBOopmXWec-n7nuJ_5GXoDX7_7dAdiw2dzGsGg7TNtoUokYNw2_xrX

The exhibit Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World was on display

at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. 18 May–2 November 2025.