Creating a Fine Art Painting: From Research to Exhibit

by Erin E. Hunter

Erin E. Hunter’s most ambitious piece yet is “Look Closer,” a large painting of California native bees and wildflowers that anchored a 2022 solo show at the San Francisco Botanical Garden. She tells the story of its creation – inspiration to process – from the sketching, designing and painting, to presenting the piece in multiple formats to various audiences.

“… I had long observed the curious fact that people will look closely at something an artist has taken pains to paint faithfully when they will not give more than a passing glance to the thing itself, which in many cases is more beautiful and interesting. It is as though they say to themselves, ‘As someone bothered to paint it, it may be worth looking at.” —John Cody, Wings of Paradise: The Great Saturniid Moths.

Figure 1: “Look Closer” final art, 40” x 30” acrylic on Arches watercolor paper, ©2021 Erin Hunter

Like most illustrators, I loved to draw as a kid. I read field guides and picture books, wishing I could draw and paint like a professional artist. I played with patterns, making designs within a circle using a compass or coloring squares of graph paper with bright jewel tones. As a traveling college student, I fell in love with the repeating architectural motifs of Spain’s Alhambra and the rose windows of Gothic French cathedrals. In my classes, I fell for typography and majored in graphic design. I learned to use my eye for symmetry and balance to combine text and imagery, and got interested in creating my own images as an illustrator. After working as a graphic designer and then freelancing in New York, I joined the science illustration program at UC Santa Cruz (now at Cal State Monterey Bay). It was thrilling to explore the detailed drawing and painting that I’d always loved, while being amongst knowledgeable and talented peers.

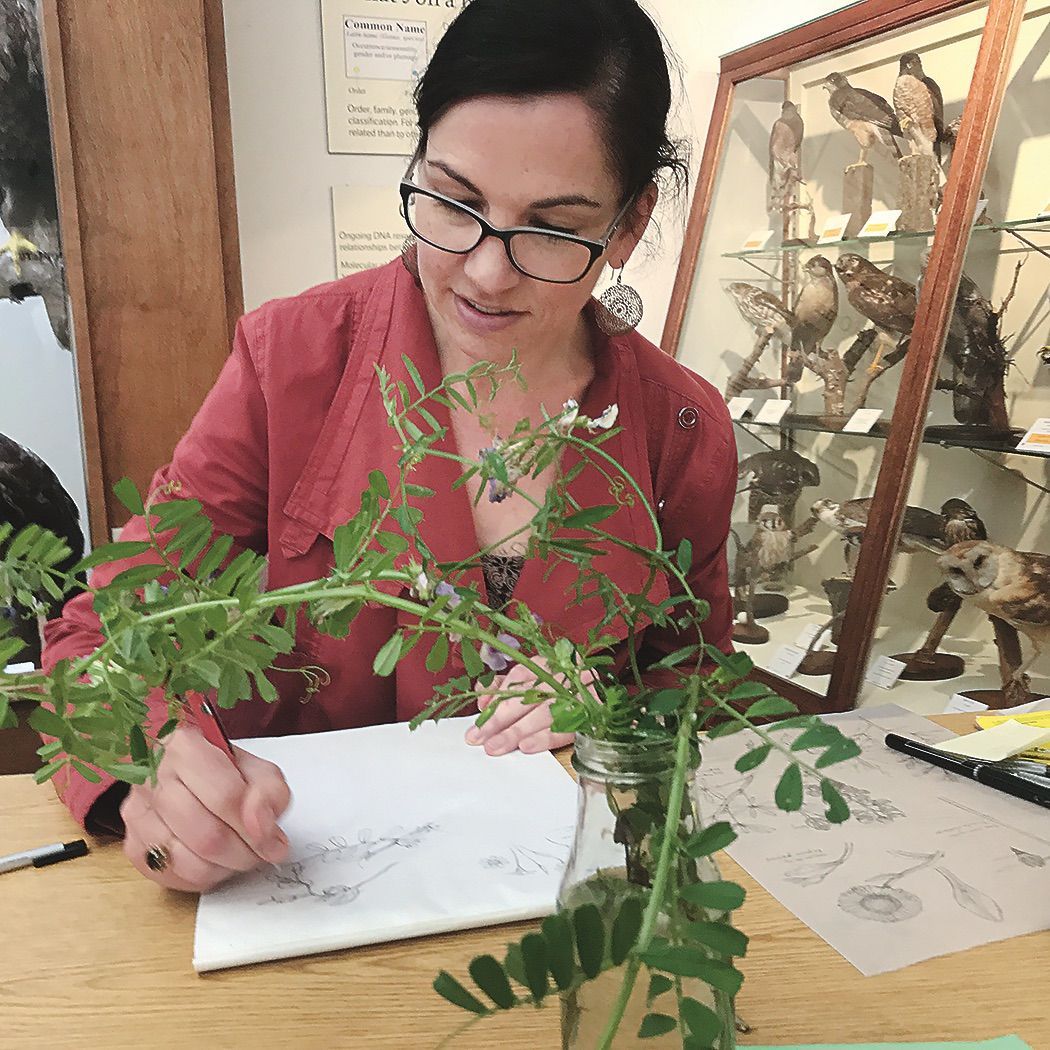

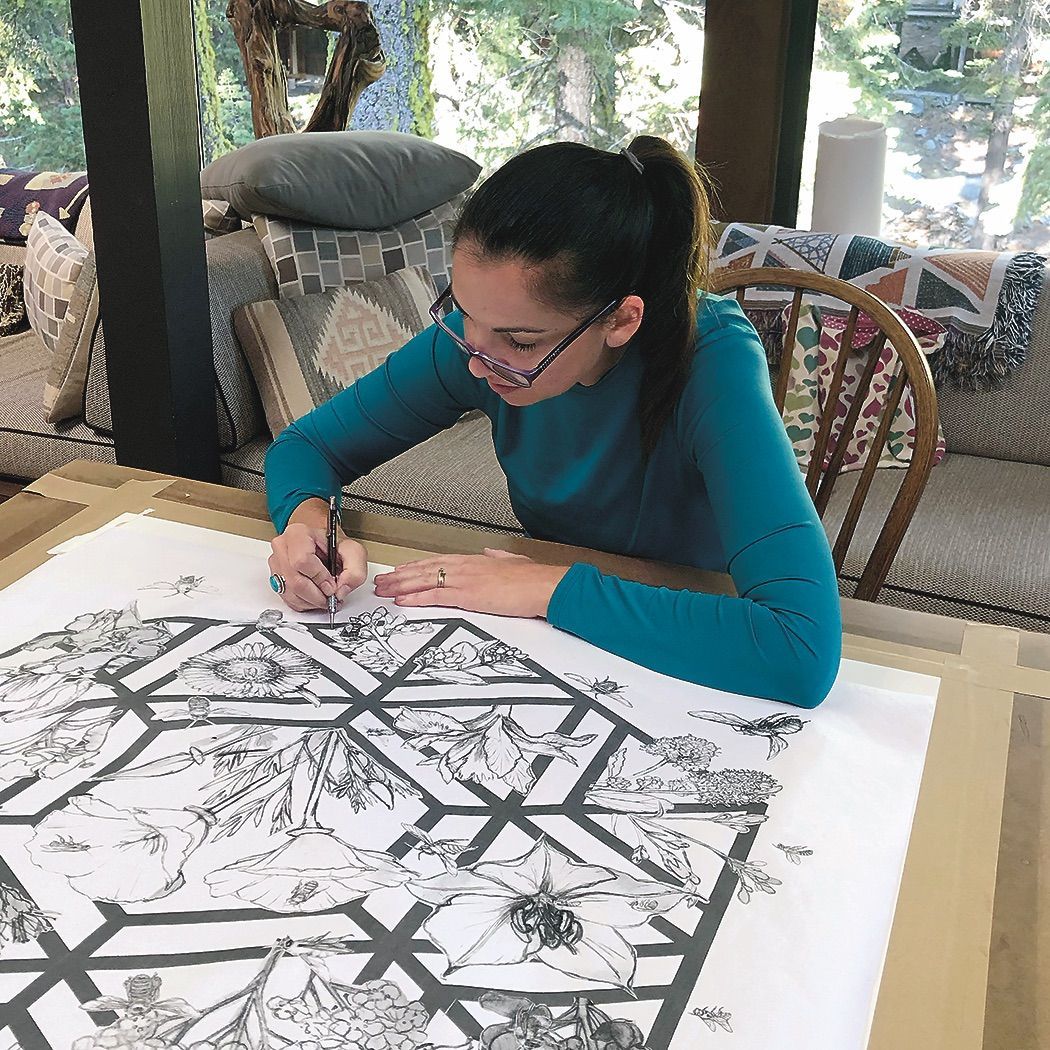

New ParagraphFigure 2 : Sketching plant specimens at the California Native Plant Society’s annual wildflower show, hosted by the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History.

I came to the science illustration program without a degree in fine art or science. What I did have was curiosity and willingness to learn. My teachers and classmates generously caught me up on things like scientific naming conventions and painting a smooth watercolor wash. Soon, I was painting portraits of plants and animals, mostly cultivated flowers and exotic birds and mammals. After my classmate, Erika Beyer, recommended the wonderful book The Forgotten Pollinators by Stephen L. Buchmann and Gary Paul Nabhan, I began combining wild plants with their native pollinators in my pieces—the first was a pair of orange-breasted sunbirds atop a pincushion protea. The plant is a common landscaping plant along the California coast, where I live. But until I read The Forgotten Pollinators, I had never wondered “Where are these plants from? Who pollinates them in their native habitat?”

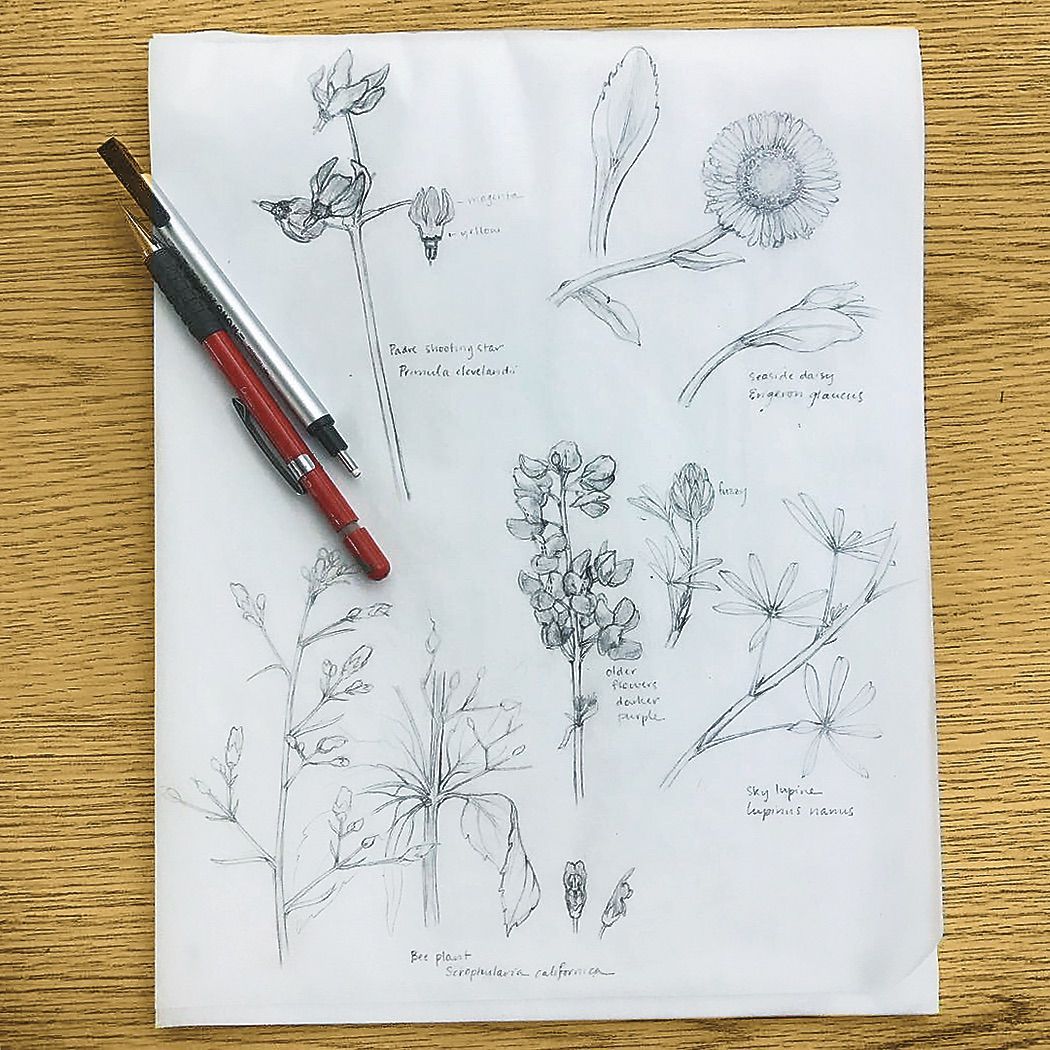

Figure 3: Plant sketches on tracing paper.

Whenever possible, I sketch plants from life; these were sketches from the wildflower show. I started painting more portraits of the African or Australian plants common in California but pollinated by perching birds in their home habitats. I also interned as a botanical illustrator at Cal Academy, creating a botanical plate of a California wildflower with its own bird pollinator: migrating Costa’s hummingbirds visit chuparosa, or Justicia californica, as they move from Mexico through California. Later, I joined the California Native Plant Society (CNPS) and focused my artwork on local flora and fauna, particularly pollinating insects.

While happily working as an illustrator, I started thinking more like a fine artist with my personal work. In the science illustration program, I had learned about Margaret Mee and John Cody, painters who used their art and knowledge of the natural world to attract attention to ecological issues that mattered deeply to them. I wanted to do the same, especially as I learned more about habitat loss for native wildflowers and pollinators in my home state.

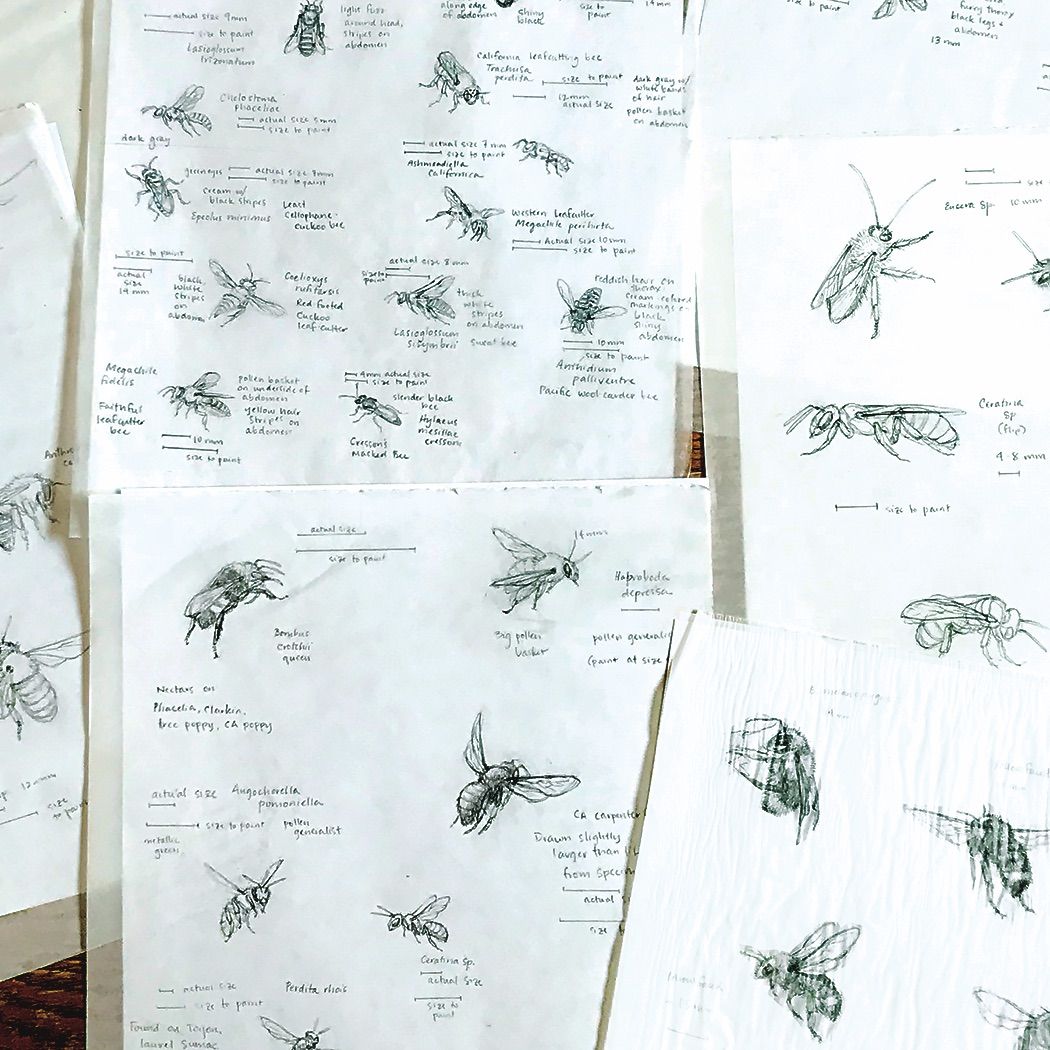

After completing a rose window-style painting of local hummingbirds and wildflowers, I was ready to do another fine art pollinator painting that focused on California’s native bees. Many of us can identify honeybees and maybe bumblebees, but not the wild array (1,600 species!) of solitary bees that live in California. My research was great fun. I sketched bee-friendly wildflowers at the local CNPS wildflower show (Fig. 2 and 3). I read books and looked at specimens. I emailed naturalists and bee scientists for suggestions, and I mooned over bee photos. I saw huge, 3-centimeter carpenter bees and tiny solitary bees only 5 millimeters long; metallic green and blue bees; bees with furry bellies and others with tiny leg tassels. I wanted to paint them all, but eventually I chose a tidy percentage of 40 bee species—that’s 2.5% of California’s 1,600 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Bee sketches and notes on tracing paper. My list of California native bees came from a record of observed bee species from Hastings Natural History Reservation.

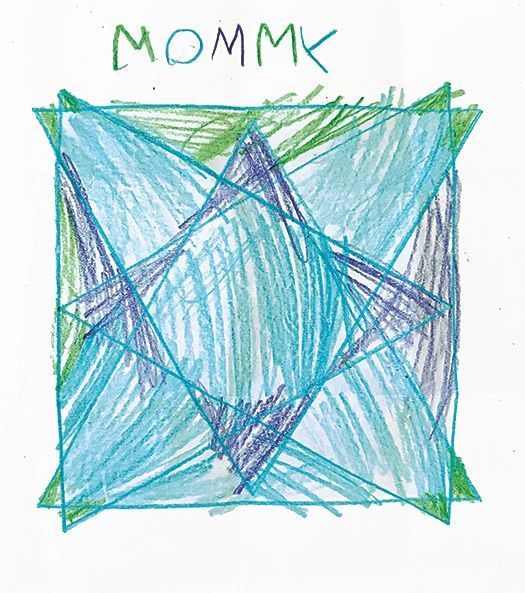

My list of California native bees came from a record of observed bee species from Hastings Natural History Reservation.The layout initially stumped me. Then one day, my daughter came home from preschool with a tessellated design of triangles that she’d created (Fig. 5). I was inspired. I played around with designs in Adobe Illustrator® until I landed on a hexagonal design that seemed bee-ish and would accommodate my wildflowers. I printed out my tessellation, photocopied my flower sketches, and cut them out. I moved the flowers around on my kitchen table and taped them down once I settled on placement (Fig. 6).

Figure 5: I found design inspiration in my daughter’s school art project.

Figure 6: Using sketch photo copies, I cut out and composed the placement of the elements at twice life size; later, I scaled up to three times life size.

When I started sketching bees, I realized that some were too tiny to cut out and tape to my layout. So, I scanned the tessellation/flower design and imported it into Illustrator. Then I imported the bees, which I’d scanned in and silhouetted in Photoshop®. This step turned out to be crucial, as it allowed me to size each bee accurately. Because some of the bees were so tiny, I decided to paint the piece at 3 times’ life-size (40” x 30”) and I got a giant, bond paper printout of the composition at my local copy shop (Fig. 7).

Figure 7 (middle right): I scanned the results and added the bee sketches in Adobe Illustrator, then sent a pdf of the composition to a local copy shop, where it was printed on bond paper.

Now that I had my composition, I needed to get it onto my preferred substrate, watercolor paper. I bought a roll of oversize Arches® watercolor paper, soaked it in my bathtub to size it, and taped it to Masonite. (I had to do this three times before I got it right! An extremely though soaking is required, longer than expected.) Then I taped my drawing on top of this and transferred my composition using graphite paper (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: Using the graphite sheet transfer technique, I placed my sketch on the watercolor paper, making final positioning corrections as needed. Note my large Masonite board, the paper had to be soaked in the extreme to make it completely pliable throughout.

It was a tedious process, but it allowed me to correct a few mistakes I encountered along the way. When it was time to paint, I blocked in the color throughout the painting in thin washes of acrylic, with the tessellation and background colors in a blue-and-gold theme. This seemed appropriate for bees, since they can perceive these colors and tend to be attracted to flowers in this color range (Fig. 9).

Figure 9: I then blocked in basic washes for the base colors, using Liquitex acrylic thinned down with water.

I continued adding layers of paint to my giant bee painting, feeling confident that I could finish before long. I had lined up a solo show at the San Francisco Botanical Garden’s Library of Horticulture, and this painting was going to be the star of the show. But then Covid hit, and I found it hard to juggle painting time and regular illustration work with young children at home full time. Sometimes I forgot what bees I was painting (Fig. 10) and I’d have to go back to my notes and re-research the bees. Eventually, the show was deferred by a year. That gave me time to finish, while also documenting my progress on Instagram. Each time I posted a step, I had an opportunity to talk about what bee I was painting and tag related accounts like @the_bees_in_your_backyard or @ pollinatorpartnership.

Figure 10 : Final painting process. Once color was blocked in with thin washes of acrylic, I added more detail with several layers of more opaque acrylic. In some areas (for example, bee legs and antennae), I used very fine-point Copic Multiliner pens or mechanical pencil for sharp lines.

After more than two years, I finished my painting. I thought I’d done the hard part, but extra-large paintings on watercolor paper are complicated. I had to find a place that could flatten any wrinkles under glass while scanning the oversized painting. And I ordered large, expensive matting and plexi to frame it for the show, but the framer said the buckled paper was fighting the mat. He found a solution to hide some of the buckling with adjusted spacing between the mat and glass, but even the framer's skill couldn't completely conceal the painting's wavy edges. The finished piece was big. When I came to pick up the project, the 47” x 45” framed piece wouldn’t fit in my car. My husband returned with his truck and we delivered it to the SF Botanical Garden (Fig. 11).

Figure 11: The extremely large (47” x 45”) final painting framed and ready to hang in the San Francisco Botanical Garden’s Library of Horticulture. Paper buckling was an issue, which was minimized when the painting was fitted in between backing and the mat window with a bit of extra spacing, but not eliminated.

“Look Closer”, together with a panel listing the names of featured bees and flowers, anchored my “Wild Nectar” show. The painting was finally on display, communicating its thesis: native bees are beautiful, important, and worthy of our protection. To promote the show, and the message of the painting, I also shared videos, wrote blog posts, and did podcast interviews about this work.

I titled the piece “Look Closer” to call the viewer to look closer at the bees I had painted, and then turn around and explore their own surroundings with the same close attention. As I shared the painting online and in person, the number one thing I heard from people was, “I had no idea there so many other bees!” I was excited to hear people respond to the painting in that way, and I hoped they would take a new awareness away with them.

Unlike some of my other pieces, “Look Closer” isn’t ideal for notecards and it’s so large that I don’t expect to sell many prints of it. But, my goal was to open viewers’ eyes to the world that surrounds them. Like John Cody, I hope that drawing attention to my larger-than-life bees will communicate their value and show their true beauty.

About the Artist: Erin E. Hunter is an artist and science illustrator who splits her time between creating pollination–themed paintings, and technical illustrations for an academic journal (Annual Reviews). Erin’s fine art paintings highlight the impact that individual species have on the wider ecosystem, bringing attention to the significance of tiny bees, dazzling hummingbirds, delicate thistles, native plants, and other ecological treasures.

This open-access article appears in the Journal of Natural Science Illustration, Vol. 54 No. 3, 2022.

Image credits:

Artist by-lines are too often buried or completely overlooked. Yet the expertise and mastery our community of visual science communicators bring to the table is unsurpassed. The images we use on our website come from our Juried Members' Exhibits over the years, as judged by a panel of experts. We name them wherever possible below each image to celebrate their excellent work and to set an example for everyone to remember that these images don't create themselves. Please visit their websites and support their work.

GET IN TOUCH

c/o Gilbert & Wolfand, PC

2201 Wisconsin Avenue, NW

Suite 320

Washington, DC 20007

info@gnsi.org

STAY CONNECTED

Subscribe to the GNSI Newsletter

Image credit: Virge Kask, member since 1979

All Content © 2023 | Guild of Natural Science Illustrators

Privacy Policy | Image Use Policy

Website powered by Neon One