Indian Botanical Art in the 21st Century

I call myself a botanical artist, but in truth I’m trained in neither botany nor art. When I first started out, about eight years ago, I was barely aware of the genre’s existence. I just wanted to paint plants.

– All illustrations © Nirupa Rao, unless otherwise noted.

You see, I grew up in the south Indian city of Bangalore. You may know it for its Information Technology (IT) industry, which has earned it the moniker “Silicon Valley of the East.” This probably brings to mind images of fast-paced lives lived in glass skyscrapers and rush-hour traffic—which is fairly accurate, but a relatively recent phenomenon. When I was growing up, Bangalore was better known as the “Garden City” of India—it boasted 70% green cover in the 1960s, which then dropped to about 40% during my childhood in the 1990s. Now, believe it or not, that number is down to less than 3%.1 This was difficult for me to witness, and, feeling powerless to stop it, I turned to drawing the trees I saw disappearing from my city’s streets.

I always had a heightened awareness of plants: Bangalore is only a few hours away from the Western Ghats or Sahyadri mountain range, which snakes up the southwest coast of India (Fig. 1). My extended family is full of botanists and horticulturalists who have worked in the region, so every school holiday we would drive down to this magical retreat filled with diverse habitats such as thick jungle, temperate grasslands, and swamps. In fact my maternal granduncle, Rev. Cecil Saldanha, was the first botanist to carry out a documentation of the flora of our home state, Karnataka, in the 1960s and 70s. Working in collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution, his team used my grandfather’s farmhouse in Hassan District as their base. My mother would tell me romantic stories of watching this entire expedition unfold. And, glossing over the undoubted tedium and hard work, I came to associate botany with adventure, discovery, and excitement.

As I grew older, I realised this wasn’t a sentiment shared by most increasingly urbanised Indians. I lost sleep over whether generations of children disconnected from nature would strive to save it when needed most, and I was desperate to somehow address this. My cousin Siddarth Machado was by then a practising botanical researcher, and so, in our early 20s, we decided to put our heads together. Combining our abilities, we created an illustrated book set in this same magical region we grew up around: the Western Ghats. We called this book Hidden Kingdom in reference to the fact that these plants are all around us, but we fail to pay them heed. They are hidden in plain sight.

Figure 1: The Western Ghats is a mountain range snaking up the southwest coast of India.

We selected species we felt would challenge readers’ basic perceptions of plants. For instance, that they have green leaves and chlorophyll. The ghost orchid (Epipogium roseum) fulfills neither of these criteria. Growing on dark forest floors where sunlight is scant, they share a symbiotic relationship with fungi that live in the orchids’ roots, which in turn derive nutrients either from dead organic matter or surrounding plants. Hence the name “ghost orchid,” inspired by the species’ deathly, spectral appearance and almost vampiric way of life.

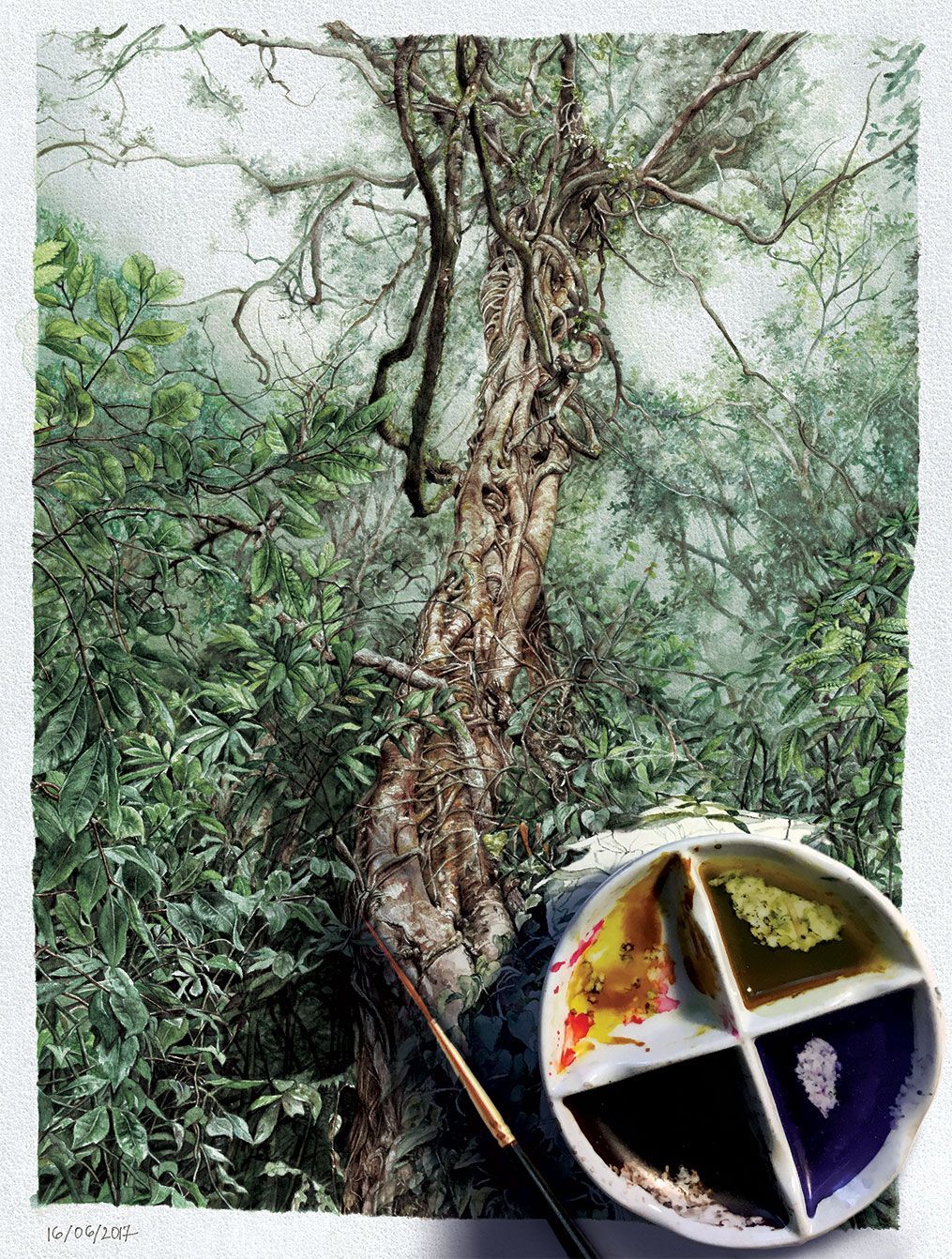

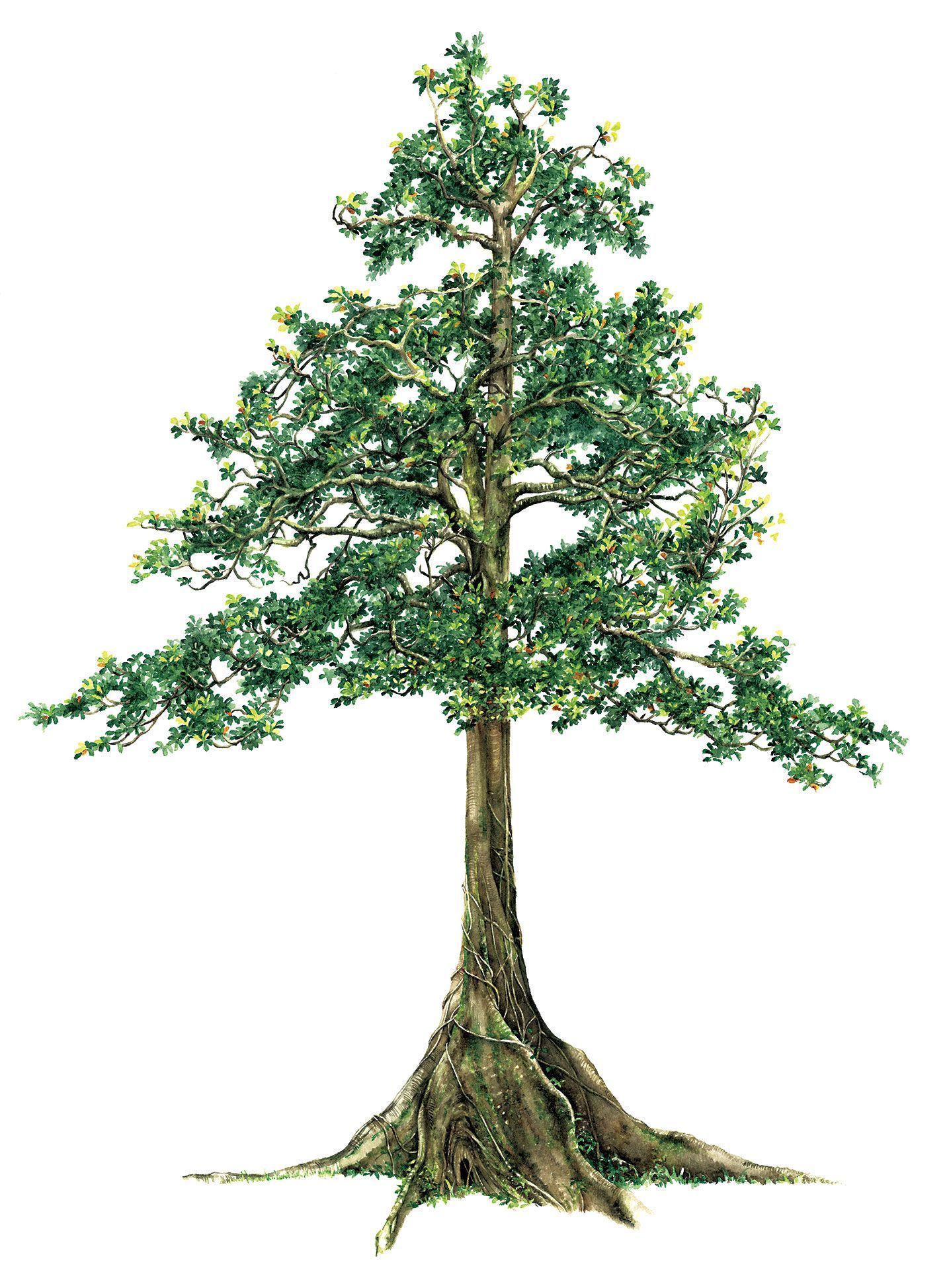

The strangler fig (Fig. 2) was a far more common but no less fascinating choice. A common sight in India, it isn’t really a species but an adaptation exhibited by members of the Ficus or fig genus. They often grow deep inside the jungles where competition is tough and sunlight is scant. So the strangler adopts a little strategy to cut in line and get ahead. Its seeds are dispersed by birds who drop them among the branches of existing trees. The little sapling will germinate atop a host tree, sending its branches upward to the sun, while its roots creep down below—all the while strangling its host tree, often to death. If the host tree dies and rots away, the strangler will persist as a hollowed out column of roots and branches.

Figure 2: A strangler fig reaching up for the sun (from Hidden Kingdom: Fantastical Plants of the Western Ghats).

We’re so used to thinking of plants as immobile, passive beings, aren’t we? But I began to see that it is this very rootedness that makes them fascinating— leading them to adapt to threats and opportunities in ingenious ways that boggle the imagination. Like these beautiful bejeweled, alien-like sundews (Fig. 3). They grow in soils with poor nutrient levels, so they supplement their diets by luring, capturing, and ingesting insects using mucilaginous glands on their leaf surfaces. Small insects are attracted by the sweet secretions of these glands, but once they come in contact, they are ensnared in the sticky substance and then it’s game over.

The experience of creating the book Hidden Kingdom

was both exhilarating and enlightening. For starters, I realised that despite my supposed botanical inheritance, I actually knew very little about plants, and even less about the Western Ghats. I had studied botany in school, of course, but our syllabus was bereft of local context. Yes, we had learned about carnivorous plants, but the example we were given was the Venus flytrap, an incredible plant native to North America. Unfortunately there was no mention of those beautiful sundews, which grow on the outskirts of Bangalore where I lived. How much more relevant and meaningful might high school botany have been if it reflected my own surroundings?

Figure 3: India’s three native sundew species—(top to bottom) Shield sundew (Drosera lunata), Indian sundew (Drosera indica) and Tropical sundew (Drosera burmannii) (from Hidden Kingdom: Fantastica Plants of the Western Ghats).

I’m sometimes asked how, as a botanical artist, I’m able to express my own individual creativity. There is a presumption behind this that botanical art, as a vehicle of science, is a neutral medium—carrier only of scientific information. But the more I learned of my newfound profession, the more I realised this was far from the truth. In fact, in India botanical art is conventionally known as “Company Art” or “Company kalam”—a reference to its association with the Dutch or British East India Companies that once colonised the Indian subcontinent.

During the modern colonial period, as European travel and conquest of various parts of the globe increased, so too did the fascination with entirely new, seemingly exotic flora. Naturalists, botanists and artists often accompanied explorers on their journeys. The HMS Endeavour, for instance, set sail from England in 1768—ostensibly, a “research vessel” which we now know was also tasked with a secret mission: to locate and claim the so-called “unknown land of the South”—Australia—for the British crown.2 Along with the naturalist Joseph Banks, the ship also carried artist Sydney Parkinson. He lived and worked aboard the ship, studying specimens and drawing day and night, battling off swarms of flies which ate his paints as he worked. He eventually died of dysentery before they managed to return to England. Such was the value attached to natural history illustration—it was a technology used to systematically catalogue the natural world in the service of both science and empire—a history with which botanical art is inextricably linked.

In India, most of these botanical art collections were commissioned by Company officials for European audiences keen to catalogue the flora of their colonial possessions, and so even today the work itself is treated as being foreign—despite the fact that its subjects, Indian flora, hail from India, as did most of the artists, who usually went unnamed (Fig. 4). And yet, if we look closely at this work, it’s clear that this art form wasn’t just a foreign import: local artists brought with them the techniques of Rajput and Mughal miniatures, the styles of Tanjavur

moochies and

gudigars, combining them with a more European treatment of perspective, volume, and recession.3,4 Every one of these images contains not only the botanical fact of a plant, but a complex well of history and meaning.

Figure 4: Plants of the coast of Coromandel: Selected from drawings and descriptions presented to the hon. court of directors of the East India Company by William Roxburgh (1795) from the Missouri Botanical Garden's Rare Books Collection.

A: Ceropegia acuminata, B: Periploca esculenta, C: Lagerstroemia reginae (now Lagerstroemia speciosa)

While we have very little information on Company artists, there is mention in some collections of the names ‘Rungiah’ and ‘Govindoo’. These names are not very revealing of their background or ethnicity, but certain clues have led historians to a group of south Indian painters known as ‘moochies’, based originally in Tanjore. Skilled in making religious and devotional paintings, they pivoted to the natural history drawings required by botanists and zoologists during British times. Historians similarly speculate that other paintings may have been made by ‘gudigars’ or sandalwood-carvers, who were also painters.

Early on in my career, I was lucky enough to meet two ecologists, Divya Mudappa and TR Shankar Raman, who live and work in the Valparai region of the Western Ghats—an area dominated by tea estates established by the British in the 19th century. In the process, vast forests were cleared to create plantations. They are now run by Indian corporations who leave those parts of their land that are unsuitable for cultivation ostensibly wild, but in practice are often dominated by tree species that were brought to India from South America or the Caribbean in the colonial period to beautify the landscape. Unfortunately, these species don’t serve the needs of local fauna. So Divya and Shankar Raman work towards encouraging landowners to grow native species on uncultivated land in an effort to create corridors of true forest connecting plantations.5,6,7

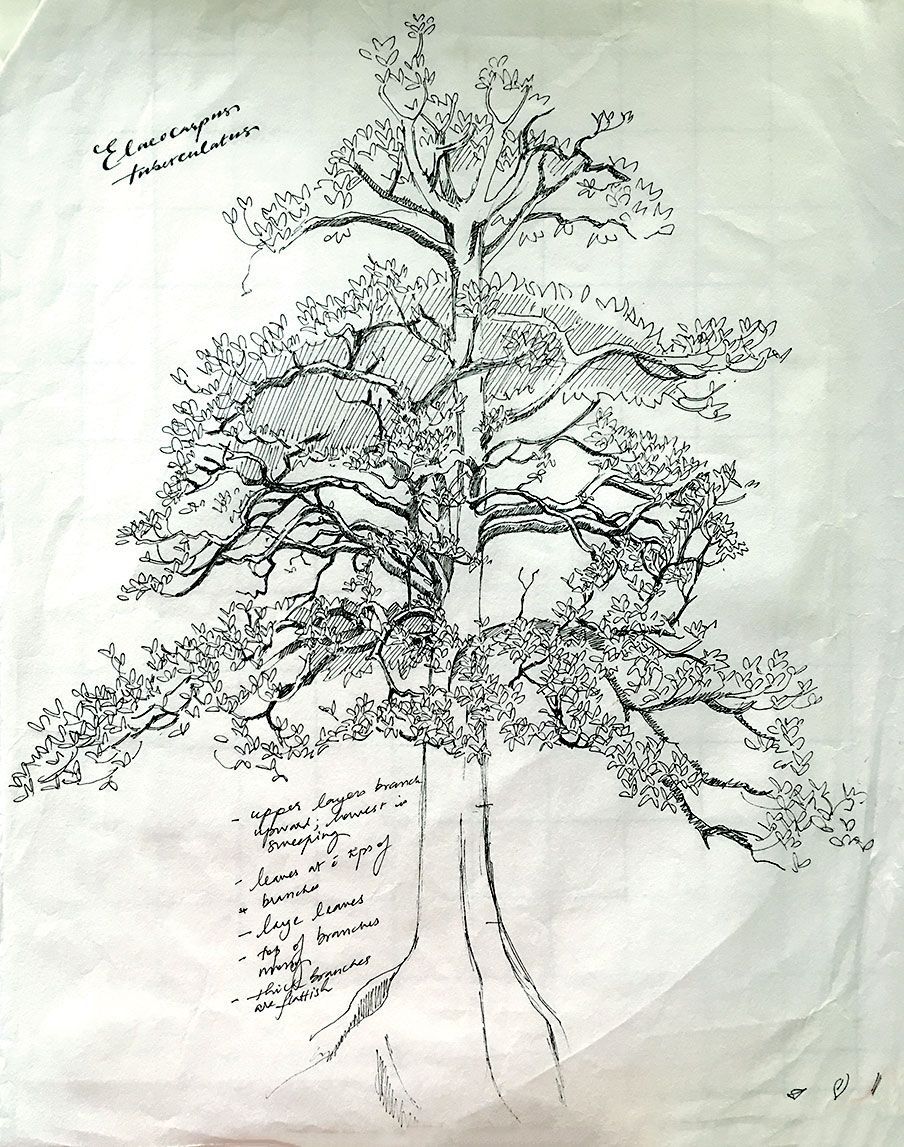

They were looking to visually document these trees in some way, but the photographers they approached came up empty-handed. These species grow up to 43 meters tall, making them impossible to capture in a single camera frame. Besides, the surrounding foliage is too dense to clearly isolate a single specimen. So together, we decided to give good old painting a shot.

In truth, even while standing before them it was tough to see the entire tree. Instead, I’d study its buttress up close, then climb up a hill to see its crown rising above the canopy. With Divya and Shankar Raman’s help, we’d imagine the intervening bits, stitching it all together into one drawing. Over two years, we documented thirty of the region’s most iconic trees, along with their fruit, flowers, seeds, and leaves. For those who don’t know the jungles as well as these naturalists, these drawings are probably the only way they’ll see these trees in their entirety (Figs. 5 and 6).

Through this process, I began to see these jungles differently. The landscape I had been visiting nearly every year since I was born—a region I thought I knew so well—morphed from an undifferentiated sea of green into individual species with individual characters. This had been a seminal moment in my own career—a moment of awakening, when my eyes were opened to what had been hidden all around me in plain sight.

Figure 5: Rough sketch of an Elaeocarpus tuberculatus tree, drawn on site.

Figure 6: Elaeocarpus tuberculatus final painting from the book Pillars of Life: Magnificent Trees of the Western Ghats.

Wanting to recreate this sensation, I decided to push the genre of botanical art far beyond its conventional limits. I wanted to breathe life into a landscape… to, well, animate it. Putting together a team of writers, researchers and animators, we created a short film called Spirit of the Forest. It tells the story of a little village girl who, through a magical encounter with a forest spirit, comes to see her home and traditions very differently. While taking a shortcut home from school, she stumbles upon a sacred grove: pockets of forest found all over India that have been protected by local communities for centuries, using folklore grounded in scientific principle.

This particular grove happens to be an endemic Myristica or wild nutmeg swamp (Fig. 7). Besides its wonderful tangle of aerial roots popping up above the ground, what’s fascinating about these swamps is that their evolution parallels the very formation of the Indian subcontinent. Scientists suggest that key Myristica species may date back to the breakup of Gondwanaland, when dinosaurs roamed the earth, and India was drifting towards its present position on the world map.8 As the little girl journeys through this incredible history, she realises that the seed she holds in her hand is not just a trivial plaything, but a kernel that holds within it the past, present, and future. An infinite, deep well of meaning.

Figure 7:

A still from Spirit of the Forest showing a

Myristica fatua tree along with endemic fauna like the Malabar giant squirrel, lion-tailed macaque,

Myristica swamp tree frog,

Myristica sapphire damselfly and Malabar tree nymph butterfly.

Of course, this would not be the first animated film set in the Indian wild—Jungle Book easily comes to mind. But as much as I love the film, you’d be hard-pressed to find an orangutan like King Louie from India, to say nothing of the largely generalised background scenery. With our film, we set out to feature some of the lesser known plants and animals that actually live here (Fig. 8). Visiting them onsite, I used these studies to hand-paint botanically accurate backgrounds for the film. I used the same techniques I had developed drawing trees with Divya and Shankar, but adapted them to suit an entire landscape. Botanist Navendu Page helped me to understand the land’s logic: which species were swamp-adapted and grew upon the water, or which species were swamp associates with only partial flood tolerance, therefore merging with the surrounding evergreen forests.

Figure 8: Movie poster, Spirit of the Forest.

The film’s story is composed of ecological tales derived from contemporary scientific research: for example, recent fieldwork has identified that hornbill birds are no longer the primary seed dispersers for nutmeg, as they often drop seeds in areas that once were swamps but have now been converted for agriculture or transport. Instead, researchers discovered tiny crabs burying seeds in their burrows, where they remain dry and germinate when conditions are ideal.9 This forms the message of hope at the film’s conclusion: the chance for a new culture around plants to take root.

We continue to screen the film in schools around the country, hoping to show Indian children how the jungles of their own landscape came to be. It is that familiarity which, when celebrated, turns to love, which can then turn into an urge to protect.

I think botanical art in the 21st century—despite or even because of its history—can help us reflect upon our own landscape and surroundings. To me, this kind of representation isn’t necessarily about patriotism or what belongs to us, because the natural world belongs to no one. It is about understanding our own context, with all its nuance and individuality, because it is ultimately our duty to love and protect it.

References

- Satellite images show green cover of Bangalore reducing alarmingly fast. (n.d.). Research Matters. https://researchmatters. in/article/satellite-images-show-green-cover-bangalore-reducing-alarmingly-fast.

- HMS Endeavour 250. (n.d.). Natural History Museum. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/hms-endeavour-250.html

- Reddy, S. (n.d.). Ars Botanica: Refiguring the Botanical Art Archive. Marg, December 2018–March 2019 (The Weight of a Petal), 15. ,4

- Noltie, H.J., "Moochies, Gudigars and Other Chitrakars: Their Contribution to 19th-century Botanical Art and Science.." The Free Library. 2018 The Marg Foundation 18 Nov. 2023 https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Moochies%2c+Gudigars+and+Other+Chitrakars%3a+Their+Contribution+to...-a0571836876

- T R Shankar Raman, Swati Sidhu, Hari Sridhar, Divya Mudappa, Vena Kapoor, Eleni K Foui, Claire F R Wordley, P Jeganathan, Ganesh Raghunathan, Akshay Surendra, T R Shankar Raman, Swati Sidhu, Hari Sridhar, Divya Mudappa, Vena Kapoor, Eleni K Foui, Claire F R Wordley, P Jeganathan, Ganesh Raghunathan, & Akshay Surendra. (2019, September 5). Wildlife in rainforest fragments. Nature Conservation Foundation - India. https://www.ncf-india.org/western-ghats/ wildlife-in-rainforest-fragments

- Divya Mudappa, T R Shankar Raman, Atul Arvind Joshi, Divya Mudappa, T R Shankar Raman, & Atul Arvind Joshi. (2014, May 27). Whittled-down woods. Nature Conservation Foundation - India. https://www.ncf-india.org/western-ghats/whittled-down-woods

- Chandran, M. D. S., & Mesta, D. K. (2001). On the conservation of the Myristica swamps of the Western Ghats. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259151683_On_the_conservation_of_the_Myristica_swamps_ of_the_Western_Ghats

- Krishna, S., & Somanathan, H. (2014). Secondary removal of Myristica fatua (Myristicaceae) seeds by crabs in Myristica swamp forests in India. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 30(3), 259-263.

- Jain, N. (2019, Nov 4). New species remain hidden in the myristica swamps of the Western Ghats. Mongabay.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Nirupa Rao is a botanical illustrator whose work is inspired by close collaboration with natural history scientists. A National Geographic Explorer and Fellow, Nirupa is the youngest artist featured in Kew Botanical Garden's Indian Botanical Art—An Illustrated History. She has illustrated two books: Hidden Kingdom—Fantastical Plants of the Western Ghats and Pillars of Life—Magnificent Trees of the Western Ghats, and the cover of Amitav Ghosh's latest novel, Gun Island. She co-directed a short animated film set in the Myristica swamps of south India titled Spirit of the Forest, screened at Annecy 2023. She was also 2022’s artist-in-residence at Harvard University’s Dumbarton Oaks.

niruparao211@gmail.com

www.nirupa-rao.com

Image credits:

Artist by-lines are too often buried or completely overlooked. Yet the expertise and mastery our community of visual science communicators bring to the table is unsurpassed. The images we use on our website come from our Juried Members' Exhibits over the years, as judged by a panel of experts. We name them wherever possible below each image to celebrate their excellent work and to set an example for everyone to remember that these images don't create themselves. Please visit their websites and support their work.

GET IN TOUCH

c/o Gilbert & Wolfand, PC

2201 Wisconsin Avenue, NW

Suite 320

Washington, DC 20007

info@gnsi.org

STAY CONNECTED

Subscribe to the GNSI Newsletter

Image credit: Virge Kask, member since 1979

All Content © 2023 | Guild of Natural Science Illustrators

Privacy Policy | Image Use Policy

Website powered by Neon One